From Right/Wrong to Decided

How couples can move beyond adversarial thinking without losing their standards

Sarah and Mike are arguing about money again. She thinks they should save more aggressively for their kids' college funds. He believes they're already saving enough and should focus on enjoying life while the children are young. Each has compelling reasons. Each feels frustrated that their partner "just doesn't get it." And each is absolutely convinced they're right… and their spouse is wrong.

Sound familiar?

This scenario plays out in millions of relationships every day, not just about money, but about parenting styles, career priorities, how to spend weekends, where to live, how much time to spend with extended family. The topics change, but the pattern remains remarkably consistent: two people who love each other get locked into a right-versus-wrong mentality that leaves both feeling unheard and disconnected.

If you've been in this situation, you've probably heard advice to "see things from your partner's perspective" or "remember that you're both entitled to your opinions." But here's what often happens next: one or both partners resist this advice because it feels like giving up on what matters to them. They worry that acknowledging different perspectives means "anything goes,” that important values will be abandoned in the name of keeping the peace.

This resistance makes perfect sense. When you believe something is truly important — whether it's financial security, quality time with family, or how to raise children — the idea that it's just "one perspective among many" can feel like a betrayal of your deepest values.

But what if I told you that this whole framework is a trap? What if the choice between "I'm right, you're wrong" and "everything is relative" is actually a false choice that keeps couples stuck in unnecessary conflict?

The Relationship Trap: When Love Becomes a Courtroom

Most couples don't start out adversarial. In the beginning, differences feel interesting, even attractive. She's spontaneous where he's planned. He's detail-oriented where she sees the big picture. These differences create a sense of completeness—together, you're more than the sum of your parts. As I discuss in my System, you find you are complementary.

But somewhere along the way, those differences that once felt complementary start feeling threatening. What changed?

The trap begins when couples unconsciously shift from being teammates navigating life together to being opponents in a “courtroom,” each trying to prove their case. In this courtroom mentality, there can only be one winner. If your partner is right, then you must be wrong. If their perspective has merit, yours must be flawed.

This adversarial thinking creates what I call "positional warfare" in relationships. Like armies dug into trenches, each partner becomes entrenched in their position, focused more on defending their territory than on finding a solution that works for both. The relationship becomes less about "How do we solve this together?" and more about "How do I prove I'm right?"

Consider Sarah and Mike again. In the courtroom of their marriage, Sarah presents her case: "We need to save more because college costs are skyrocketing, and we don't want our kids burdened with debt." Mike counters: "We're already saving responsibly, and childhood memories are priceless. We can't get these years back."

Both arguments are compelling. Both come from love and genuine concern for their family's well-being. But in the courtroom framework, only one can be "right." So they dig in, gathering evidence, marshaling arguments, and growing increasingly frustrated with their partner's inability to see the obvious truth.

The tragic irony is that this right-versus-wrong mentality, designed to protect what they value most, actually undermines it. In their effort to win the argument, they're losing their connection. In trying to be right, they're damaging what's most important to both of them: their relationship.

The False Choice That Keeps Us Stuck

When couples recognize that the right-versus-wrong approach isn't working, they often encounter advice that sounds something like this: "You need to accept that you just see things differently. There's no right or wrong here—just different perspectives."

For many couples, this advice triggers immediate resistance. And understandably so. When you believe deeply in something — whether it's the importance of financial security, quality family time, or how to discipline children — being told it's just "one perspective among many" can feel invalidating and dangerous.

Sarah might think: "Are you telling me that wanting to secure our children's future is just my opinion? That it's no more valid than wanting to spend money on vacations?"

Mike might respond: "So caring about making memories with our kids while they're young is just my perspective? Does that mean it doesn't really matter?"

This is where couples get trapped between two extremes:

Extreme 1: Rigid Righteousness "I'm right/you're wrong, and I need you to see that." This extreme offers certainty and maintains personal values, but destroys connection and prevents collaborative problem-solving.

Extreme 2: Relativistic Resignation "Everything is just different perspectives, so nothing really matters." This extreme preserves peace temporarily, but feels like abandoning important values and standards.

Neither extreme works. The first destroys relationships. The second feels like surrendering everything you care about.

But here's what most people don't realize: this is a false choice. You don't have to choose between having standards and having connection. You don't have to pick between caring about important things and respecting your partner's perspective.

There's a third way. A path that honors both your values and your relationship. But it requires understanding that "we see things differently" isn't the destination. It's the bridge.

The Bridge: From Positions to Possibilities

When couples get stuck in right-versus-wrong thinking, they're usually defending positions… concrete stances about what should happen. "We should save more." "We should enjoy life now." "We should discipline this way." "We should spend holidays there."

Positions feel important because they often represent deeper values and needs. Sarah's position about saving isn't really about money. It’s about security, responsibility, and protecting their children's future. Mike's position about spending isn't really about vacations. It’s about connection, presence, and creating lasting memories.

But here's the problem with defending positions: they're fixed, specific, and usually mutually exclusive. If you implement Sarah's position fully, Mike's needs get ignored. If you go with Mike's approach, Sarah's concerns get dismissed.

This is where the bridge comes in. "We see things differently" isn't meant to make everything relative or unimportant. It's meant to create space to move from defending fixed positions to exploring the values and needs underneath those positions.

When Sarah says, "Help me understand your perspective," she's not agreeing with Mike or abandoning her own values. She's creating space to discover what's really driving his position. When Mike responds with curiosity rather than defensiveness, he's not giving up on what matters to him. Instead, he’s opening the possibility that there might be a solution neither of them has thought of yet.

The bridge of different perspectives serves a crucial function. It transforms the dynamic from adversarial to collaborative. Instead of two opponents trying to win, you become two teammates trying to solve a puzzle together. The puzzle is: "How do we honor what's important to both of us?"

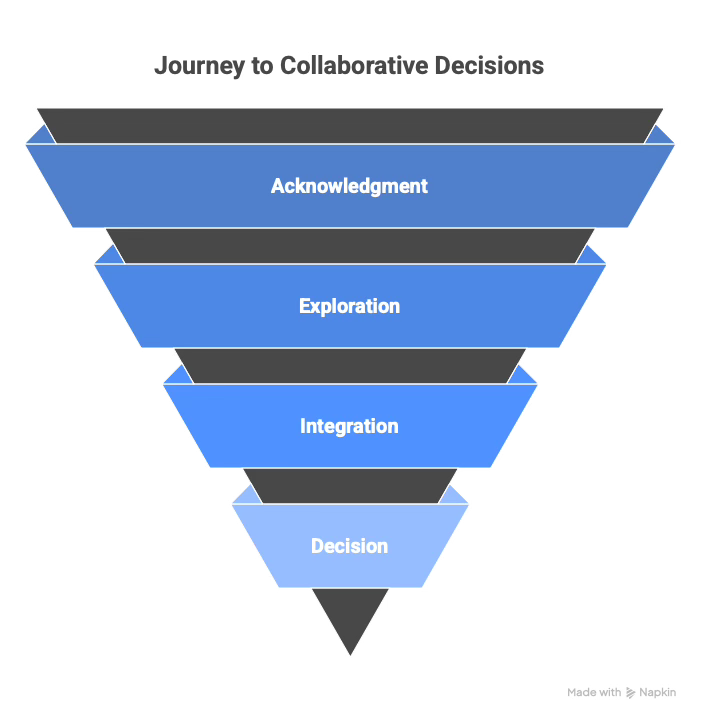

The Journey from Different to Decided: A Five-Step Process

Understanding that "different perspectives" is a bridge, not a destination, opens up a powerful process for moving from conflict to connection to creative solutions. Here's how Sarah and Mike — and you — can navigate from being stuck in right-versus-wrong to reaching decisions that honor both partners:

Step 1: Positions → "I'm right, you're wrong"

This is where most couples start when they hit conflict. Each person has a clear position about what should happen, and each believes their position is obviously correct. This step isn't inherently bad. After all, positions often represent important values and legitimate concerns. The problem comes when couples get stuck here.

Sarah's position: "We need to cut discretionary spending and put more money toward college savings."

Mike's position: "We're already saving enough. We should use some of our discretionary income for family experiences."

At this stage, each person is focused on proving their position is right rather than understanding why their partner holds a different view.

Step 2: Bridge → "We see this differently"

This is the crucial pivot point. Instead of continuing to argue about who's right, one or both partners acknowledges that they're approaching this issue from different angles. This acknowledgment isn't agreement. It’s recognition.

This might sound like:

"I can see we have really different feelings about this."

"It seems like we're both coming at this from different places."

"Help me understand how you're thinking about this."

The key is that this acknowledgment comes from curiosity rather than resignation. You're not saying, "Fine, we disagree, let's drop it.” Or the “We’ll have to agree to disagree.” You’re saying, "We disagree, and that's interesting. Let's explore why."

Step 3: Exploration → "What matters to each of us here?"

This is where the real work happens. Instead of continuing to defend positions, both partners get curious about the values, needs, fears, and hopes that drive those positions.

Sarah might discover that her push for more savings comes from growing up in a family that struggled financially, and she's determined that her children won't face the same stress she did. The position is about money, but the deeper need is about security and protection.

Mike might realize that his emphasis on family experiences comes from his own childhood, where his parents worked constantly and he craved more connection with them. His position is about spending, but the deeper need is about presence and bonding.

At this stage, something beautiful often happens. Even when partners don't agree with each other's positions, they can usually understand and respect each other's underlying needs. Sarah may not think they need more family vacations, but she can absolutely understand Mike's desire to be present and connected with their children. Mike may not think they need to save more aggressively, but he can deeply appreciate Sarah's commitment to their children's security.

Step 4: Integration → "How do we honor both needs?"

Now comes the creative part. With a clear understanding of what's driving each person's position, the couple can start brainstorming solutions that address both sets of needs. This is where the magic happens, where couples discover that honoring both perspectives often leads to solutions that are better than either person's original position.

Sarah and Mike might discover several possibilities:

They could look for ways to create meaningful family experiences that don't require significant spending — camping trips, hiking adventures, regular family game nights.

They might decide to increase college savings by 50% of what Sarah wanted while allocating the other 50% to a family experience fund.

They could commit to one modest family trip this year while also taking on a side project or freelance work to boost college savings.

They might explore whether some college saving could be offset by encouraging their children to pursue scholarships or attend community college for the first two years.

Notice that none of these solutions is exactly what either Sarah or Mike originally proposed. But all of them address Sarah's deep need for her children's security and Mike's deep need for family connection.

Step 5: Decision → "What works for us as a team?"

The final step is choosing a specific path forward that both partners can genuinely support. This doesn't mean both people are equally enthusiastic about every aspect of the decision. But it does mean that both feel heard, respected, and confident that their core needs are being addressed.

Sarah and Mike might decide to increase their college savings by a moderate amount while committing to monthly family adventures that focus on connection rather than cost, like hiking, visiting free museums, having regular camping trips in their backyard. They're not implementing either person's original position fully, but they're addressing what mattered most to both of them.

The key insight here is that the final decision isn't a compromise in the traditional sense. It’s not about each person giving up half of what they want. Instead, it's an integration that honors the deeper needs underneath their original positions.

Why This Process Works: The Psychology of Partnership

This five-step journey from "Different to Decided" works because it addresses several crucial psychological needs that traditional right-versus-wrong approaches ignore:

The Need to Be Heard When partners defend positions, they're often really fighting to be understood. The bridge step, acknowledging different perspectives, creates space for each person to feel genuinely heard before moving toward solutions.

The Need for Agency Nobody likes feeling forced to accept someone else's solution. By exploring underlying needs together and brainstorming solutions collaboratively, both partners maintain agency in the process. The final decision is something they've created together, not something imposed by one person on the other.

The Need for Respect Right-versus-wrong thinking implicitly communicates that one person's perspective is valid and the other's isn't. The Different to Decided process communicates that both perspectives have value, even when they lead to different conclusions.

The Need for Connection Adversarial approaches damage the relationship in service of being right. This collaborative approach strengthens the relationship while addressing the original concern. Partners end up feeling more connected, not less, even when they started from very different positions.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

As powerful as this process is, couples often encounter predictable challenges when they first try to implement it. Here are the most common pitfalls and how to navigate them:

Pitfall 1: Fake Bridge Building Sometimes one partner will say "I can see we think differently," but their tone and body language communicate "and you're obviously wrong." This isn't genuine bridge building. It’s just a more polite way of being adversarial.

Solution: Genuine bridge building requires actual curiosity. If you catch yourself going through the motions without real interest in your partner's perspective, pause and ask yourself: "What would I need to believe for my partner's position to make sense?" Then get genuinely curious about finding out.

Pitfall 2: Skipping the Exploration Some couples try to jump directly from acknowledging different perspectives to brainstorming solutions. But without understanding the deeper needs and values underneath each position, your solutions will likely miss the mark.

Solution: Resist the urge to fix things quickly. Spend real time in the exploration phase. Ask questions like: "What makes this feel important to you?" "What are you hoping will happen if we do it your way?" "What are you worried might happen if we don't?"

Pitfall 3: Compromise Instead of Integration Traditional compromise often feels like losing to both people, as each gives up half of what they want, and nobody's fully satisfied. Integration, by contrast, seeks solutions that address the underlying needs of both partners.

Solution: Instead of asking "How can we each give up some of what we want?" ask "How can we create something that gives us both what we really need?" This often requires thinking outside the original positions entirely.

Pitfall 4: One Person Does All the Work Sometimes one partner embraces this approach while the other continues operating from a right-versus-wrong mentality. This creates an unfair dynamic where one person is always accommodating while the other remains rigid.

Solution: This process works best when both partners commit to it together. If your partner isn't ready to move beyond right-versus-wrong thinking, you might need to have a conversation about how you want to handle disagreements as a couple before diving into specific issues.

Beyond Conflict Resolution: Building a Different Kind of Relationship

While this Different to Decided process is incredibly effective for resolving specific conflicts, its deeper value lies in what it creates over time: a fundamentally different kind of relationship.

Couples who consistently practice moving from positions to needs, from adversarial to collaborative, from right-versus-wrong to different-to-decided, report several profound shifts:

Increased Intimacy When partners regularly explore the deeper needs and values underneath their positions, they develop a more nuanced, empathetic understanding of each other. This deepens emotional intimacy in ways that simply being "right" never could.

Enhanced Creativity Teams that embrace different perspectives consistently outperform homogeneous groups in problem-solving and innovation. The same principle applies to couples. Partners who learn to integrate different viewpoints often discover solutions that surprise them with their elegance and effectiveness.

Greater Resilience Relationships built on collaboration rather than control are more flexible and resilient when facing external stresses. Couples who see each other as teammates rather than opponents are better equipped to handle whatever life throws at them.

Reduced Resentment Right-versus-wrong approaches often create winners and losers, which breeds resentment over time. The Different to Decided process creates solutions that both partners can genuinely support, reducing the buildup of relationship debt.

From Understanding to Implementation

Understanding this process intellectually is one thing; implementing it in the heat of actual conflict is another. Here are some practical strategies for making this shift real in your relationship:

Start Small: Don't begin with your biggest, most emotionally charged issues. Practice the Different to Decided process with lower-stakes disagreements first, like where to go for dinner, how to spend Saturday morning, which movie to watch. Build the muscle memory when the emotional stakes are manageable.

Create a Pause Ritual: Agree on a signal that either partner can use when you notice you've fallen into right-versus-wrong mode. This might be a specific phrase ("I think we're getting stuck"), a gesture, or even just calling for a five-minute break. The goal isn't to avoid the conversation but to reset the dynamic.

Practice the Language: Get comfortable with bridge-building phrases: "Help me understand your perspective," "I can see we're approaching this differently," "What feels important to you about this?" Practice saying these phrases when you're not in conflict so they're available when you need them.

Celebrate Integration When you successfully move through the Different to Decided process and reach a solution that honors both perspectives, acknowledge it. Celebrate these moments of collaboration. This positive reinforcement helps establish new patterns.

The Path Forward

Sarah and Mike's story doesn't end with one resolved conflict about college savings and family experiences. It continues with dozens of other disagreements about career decisions, parenting approaches, extended family relationships, and countless daily decisions large and small.

But having learned to move from Different to Decided, they approach these future conflicts differently. They still have strong opinions. They still care deeply about their values. They still sometimes get triggered and fall back into right-versus-wrong mode.

The difference is that they now have a path out. They understand that acknowledging different perspectives isn't about abandoning their values. It’s about creating space to honor what matters to both of them. They've discovered that the question isn't whether they see things differently (they do), but what they're going to do with those differences.

This is the real gift of moving beyond right-versus-wrong thinking: not that you'll stop having disagreements, but that your disagreements can become opportunities for deeper connection, greater creativity, and stronger partnership.

The trap of adversarial thinking promises certainty at the cost of connection. The Different to Decided process offers something better: the possibility of solutions that honor both your values and your relationship, decisions that feel right not because one person imposed them on the other, but because two people created them together.

In a world that increasingly encourages us to choose sides, to dig into positions, to prove we're right and others are wrong, couples who learn to move from Different to Decided are doing something radical. They're proving that it's possible to care deeply about things that matter while still maintaining curiosity, respect, and love for someone who sees the world differently.

That's not just good for relationships. It's good for the world.

What would change in your relationship if you stopped treating your differences as right/wrong or even opposites? What can change if you worked together as a team? That really is the goal. To find a way through the disconnect and the hurt to a committed path together. Make that choice. Then move from Different to Decided.

And if you find yourself stuck, please take a look at my Save The Marriage System.

👉 GO HERE to learn more and to grab my System.